The discovery and early development phases of pharmaceutical R&D are notoriously challenging. Success (even marked by regulatory approval, let alone meaningful sales) is a distant vision. The cost of prosecuting each project is high, and rises very rapidly as development progresses, yet the vast majority of projects – no matter how compelling initially – eventually fail.

Faced with such challenges, there is little wonder R&D productivity is so low, with each new approval costing the industry something in the region of $2billion (estimated by dividing global annual R&D spend by average annual drug approvals). It also makes selecting the optimal strategy for managing an early R&D portfolio critical, if you are going to play such a high-stakes game at all.

Unfortunately, there are few (if indeed any) other business processes to guide our strategy – certainly none with parameters so extreme. Innovation in other technologies, such as IT, may fail as frequently but typically take neither as much time nor capital to prosecute before reliable indicators of eventual success begin to mount.

Inspiration, therefore, must come from a different source.

Dungeons and Dragons (or D&D), it turns out, is an excellent model for early R&D in the pharmaceutical industry. Winning strategies for wizards and warriors are, consequently, useful guides for R&D chiefs whether in global pharma companies or virtual biotechs.

Struggling to see the parallels? Read on.

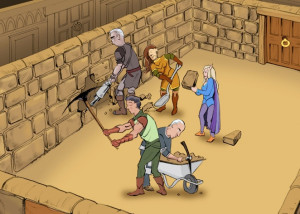

A party of doughty adventurers awake to find themselves in a prison cell somewhere in the middle of a maze-like dungeon. Stripped of their possessions by their captors, they have only one goal that counts for anything: escaping alive. Right now, though, locked in a cell that seems a distant prospect (much like approval of a preclinical drug candidate).

There are, however, intermediate goals that, while having little value in of themselves, nevertheless increase the likelihood of eventual success. Getting out of the cell, finding food, armour and weapons and staying alive while exploring the dungeon in search of the exit are essential pre-requisites for eventual escape.

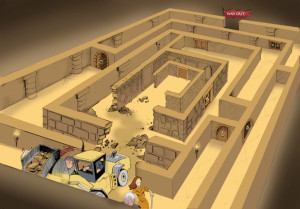

As with drug R&D, there are many plausible paths to take, and (at least initially) very little information to guide the selection of one way over another. Yet the options available at each step are completely dependent on all the steps taken up until that point. You will only find the magical armour in the locked chest if you initially went east – west lies the dragon!

While seeking the correct sequence of actions to secure escape, the party of adventurers has a strictly limited amount of resources – torches, food and stamina, for example. The game then rides upon finding a winning combination before time runs out, using imperfect information at every step.

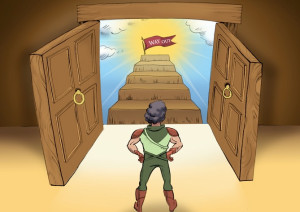

That is a perfect model for drug development. Both are represented by a sequence of decisions based on very little information, to deliver a distant goal when the intermediate milestones have very little value, and to do so before the available resources have been exhausted.

What sort of strategy is likely to be successful?

One option is to commit the available resources to one particular solution. Let’s call that “pick the winners”. Our adventurers look out the door, and decide it looks lighter and brighter to the west – so they commit every ounce of their effort to going west, no matter what. If going west turns out to be the right direction, they are going to be successful. But, of course, making such a decision on so little information means that, more often than not, its entirely the wrong direction.

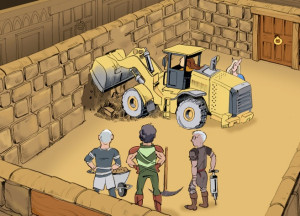

The alternative is to split up and try several possible routes, conserving the resources until the moment when it’s much clearer which direction looks the most promising. The key to success with this strategy is to gain information about the eventual way out in as many ways as possible, using as little as possible of the stockpile of torches, food and stamina.

As the adventurers start to open doors, some of them will look decidedly unpromising. The first door reveals a dragon, perhaps. The second a spiral staircase going deep into the bowels of the earth. Its important to remember that either of these routes might still be the way out. The exit door might be behind the dragon. The path out might involve going down to the deepest dungeon and then back up again somehow.

But they are still the wrong routes to take, if the party judges they have insufficient resources to complete either journey. If the dragon kills you, or you run out of torches before you re-surface, you have lost no matter which is the “correct” way out.

Our adventurers, then, rightly “kill the losers”. They eliminate from play the unpromising alternatives, and devote the resources to the remaining options. Gradually, over time, they are left with only a few plausible options – and the best possible chance that one of them leads them to safety before the lights go out.

The pharmaceutical industry faces exactly these same strategic options.

Even expensive consultants have recommended “pick the winners” as a strategy. Arguing that there is insufficient resources to pursue every possible project, the sensible approach – they claim – is to select the most promising and focus the limited resources (money and talented people) on those.

Such a strategy makes sense, though, only if there is enough information to reliably identify the winners. Focusing resources early (like committing to a direction of travel to escape the dungeon, no matter what) works if you are right about the chosen target. But early in drug discovery and development there is rarely anything like enough data to justify such a decision.

Instead, R&D managers need to focus on killing the least promising projects and keeping as broad a range of irons in the fire as possible. Doing so requires an incessant focus on keeping the cost per project as low as possible, allowing as many of these “not dead yet” options to be pursued to the next level.

As with the intrepid adventurers, some of the projects that were eliminated might, in the end, have yielded a positive outcome. But the same arguments apply: the cost of finding out if an unpromising option really is a winner can be so high that it renders the entire drug discovery and development activity uneconomic. Each failure that is pursued almost to the end of the road drains so much resource from the system that hundreds of promising, earlier stage, projects are denied their moment in the sun as a consequence.

The lessons for pharma R&D managers from D&D are, therefore, practical and actionable. Faced with demands to lower the overall R&D budget, do not cut the number of projects (which is what the “pick the winners” strategy demands); instead cut the cost per project by ensuring only the data critical for the next “kill or continue” decision is generated.

This way, you are ruthlessly filtering out projects on the basis of the information you decided in advance was the most important to inform the decision.

“Picking the winners” is inherently more attractive to the human psyche: after all, it derives success from being clever at picking the right projects. By contrast, a “kill the losers” strategy looks dangerously close to random, keeping everything going and carrying the implicit message from the R&D leaders that “we are not clever enough” to pick the best projects.

No-one likes to admit they are not smart enough to pick the winners. But when there is insufficient information available to make that call, there is surely no stigma to remaining humble. After all, like the warriors and wizards who only survive to fight another day if they make it out of the dungeon, the very existence of pharma R&D is under threat unless productivity improves dramatically over the coming years. And after more than a decade of steep declines in productivity, hubris among R&D leaders hardly seems justified. It may not be the meek who inherit the earth, but it will likely be the humble.

This piece is based on the Opening Address I delivered at the 10th Index Forum, held in Rome, Italy, in August 2014. The annual Index Forum is an invitation-only gathering of about 100 senior leaders from the global pharmaceutical, biotech and life science venture capital industries. Cartoons by Dice Design

This article by DrugBaron was original published by Forbes, and can be found here

The Cambridge Partnership is the only professional services company in the UK exclusively dedicated to supporting companies in the biotechnology industry. We specialize in providing a “one-stop shop” for accountancy, company secretarial, IP management and admin services. The Cambridge Partnership was founded in 2012 to fill a gap. Running a biotechnology company has little …