“There is more than one way to skin a cat” is a rather gruesome British idiom, but its sentiment surely applies to running a successful pharmaceutical portfolio. It is now more than a decade since Francesco De Rubertis, together with Kevin Johnson and Michele Olier, coined the term “asset-centric” investing to describe the approach to portfolio creation that still underpins the strategy at Medicxi. And today it has earned its place in the lexicon of life science venture capital, playing a key role in generating returns of investment houses across the globe.

But it is not universal. Indeed, many highly successful investors adopt strategies that are close to the opposite of “asset-centricity”, with large Series A rounds behind pipelines or platforms. And even the fathers of asset-centricity themselves have said on many occasions that the approach is not suited to all kinds of assets or opportunities.

What then determines the “right” model?

The same Monte Carlo models that a decade ago helped DrugBaron refine the concept of asset-centricty can provide insight into the conditions under which an asset-centric strategy “wins”. Doing that requires a quick review of the those models (described in much more detail here and here).

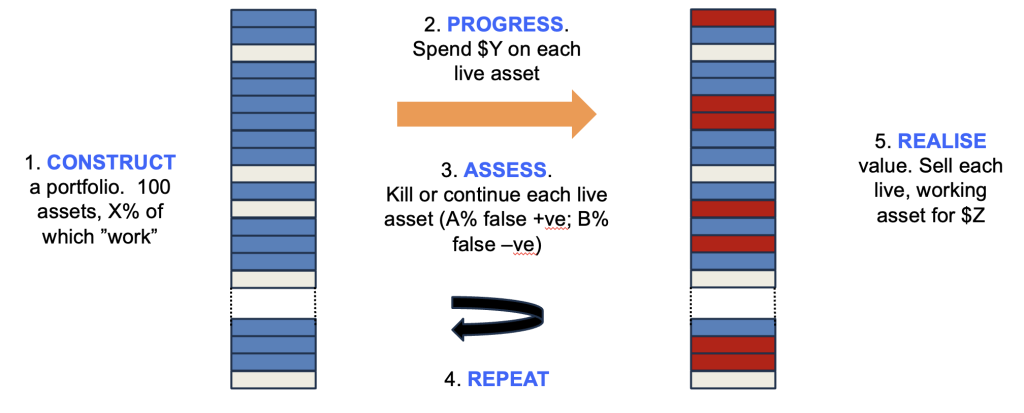

The system being modelled is shown in Figure 1. Synthetic portfolios are created in silico, where each asset has a hidden flag as to whether it “works” or not (because, in the real world, whether an asset can be successful or not is fixed before you invest – we just don’t know which ones work until after we work them up), with X% of the assets marked as working. A sum is then invested in each asset ($Y) and thereafter a decision is made whether to kill or continue the asset – and crucially this decision has a false positive rate (A%), where it keeps going assets whose hidden flag indicates eventual failure, as well as a false negative rate (B%) where it kills assets marked as “working”.

This cycle is then repeated multiple times, and once a fixed sum has been invested, the remaining live assets are monetised, with those that work delivering $Z and those that do not being worthless. The total sum realised compared to the total invested estimates the return on that portfolio. You can run the model with lots of synthetic portfolios with different conditions (X, Y, Z, A and B can be varied), comparing average and range of returns to optimise the strategy.

What this taught us that returns are most sensitive to costs, particularly during the early iterations (such that it rarely makes sense to pay extra for more information, even if it modestly improves the quality of the decision filter). It also …

RxCelerate Ltd is an outsourced drug development platform based near Cambridge, UK. We specialize in delivering an entire road map of drug development services from discovery and medicinal chemistry through to formal preclinical development and clinical up to Phase IIa. In the last five years, we have witnessed dramatic changes in the drug development …